THE LONG JOURNEY

Johnny Angel Martinez ended his search for redemption by turning himself in

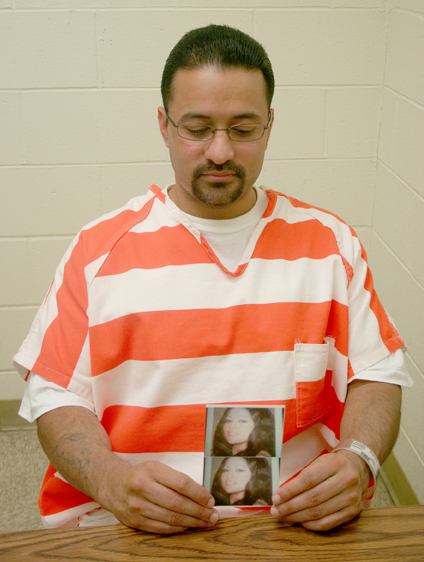

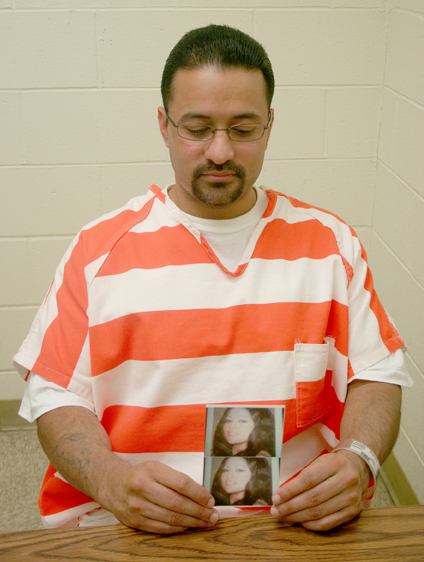

Johnny Angel Martinez holds a photo of his late mother, known as Chuca / Claudia Meléndez, The Monterey Herald

By JULIA REYNOLDS, Herald Staff Writer

Sunday, December 11, 2011

Part one of two

Part two: Man who surrendered has no regrets

Editor’s note: On Dec. 1, 2011, Johnny Angel Martinez , 34, was sentenced to 15 years to life after turning himself in to police for his role in a Salinas murder 10 years earlier. This two-part series tells the story of Martinez’s decision to face justice.

On an August afternoon last year, Johnny Angel Martinez carefully set down his cigarette, walked through the front doors of the Salinas Police Department and told an attending officer, “I need to talk to a homicide detective.”

He told the officer it had to do with a homicide he was involved in.

“Excuse me?” he recalled her saying. “Not a homicide that you know about or that you witnessed?”

No — it was one he was involved in, he said. She asked him to wait. He told her he would be right outside finishing his cigarette. Martinez knew it could be one of the last smokes he would have for years, maybe forever.

As he inhaled and listened to his MP3 player, he told himself, “Don’t leave.”

A voice inside that he had been resisting for a year told him this was the necessary conclusion to a journey that began almost a decade earlier when he was ordered to help his gang kill his own mother.

It was a journey that would lead him on a difficult search for redemption and end with a new start on life that he knew could only come from facing justice.

A tough upbringing

The 34-year-old Martinez says he was just 5 when he saw a junkie die of an overdose in his mother’s home.

“Johnny had it real hard,” says his childhood friend Angel Botello of Martinez’s upbringing in Salinas and the Central Valley.

Martinez said he never even saw a picture of his Puerto Rican father. His mother was a heroin addict and her home frequently hosted other addicts. One of young Johnny’s first jobs was running and getting the spoon and the ice, tools his mother used for treating overdoses until paramedics arrived.

Other times he showed novice users how to shoot up while the grown-ups laughed and called it cute. When he played alone, he recalls, he pretended to inject a syringe into his arm. Miraculously, he never shot heroin in his life.

A year later, he says, his mother was boosting him through open windows so he could help her rob houses. He was told that a good man provides for his family, even if that means stealing and robbing to do it.

Largely because of his mother’s addiction, he went in and out of foster homes and seemed to live two lives. Throughout his childhood, Martinez says, he was a straight-A student who eventually moved into advanced placement classes. He was a brainy boy who skateboarded and listened to heavy metal.

Former probation and parole officer Dan Villarreal, now director of the Strengthening Families program in Salinas, has known Martinez since he was 12 years old.

“Even during his incarceration in juvenile hall, group homes or the California Youth Authority … many staff wondered, ‘What is this kid doing here?'” Villarreal says.

Martinez says his mother had her own expectations for him. Known to everyone as Chuca, she would brag to friends that one day her son Johnny Angel would be an important gangster.

The family lore was that Chuca was so dedicated to the gangs of Salinas that while she was in labor, she had a relative drive her from the Central Valley so that Johnny could be born in Salinas.

He was 14 years old when, in June 1992, he held his friend Prescott Torrez’s head in his lap as the boy lay dying. He had wandered into the crossfire of rival gangs outside the Breadbox Recreation Center in East Salinas. Prescott, 15, would be the first of more than two dozen friends Martinez would see murdered over the years.

Through his teens, Martinez graduated from stints in juvenile hall to sentences in the California Youth Authority and then prison, from throwing punches in the park to brandishing guns. He also started using drugs, smoking pot and later using cocaine and methamphetamine.

As he ascended the gang’s ranks, he was eventually ordered to kill homeboys who had been deemed “no good” by the bosses, but fate always seemed to intervene at the last minute and the hits never happened.

By his early 20s, his role in the gang had become that of an ambassador. He was good at keeping up morale, directing younger gang members, and coordinating drug sales.

He convinced himself he was helping promising youngsters by getting them real jobs. He shared his apartment, his clothes — and his guns — with them.

Wrapped up in a crime

On Memorial Day Weekend in 2000, Martinez spent a day at Lake Nacimiento with a couple of gang associates. He says the others fell asleep as he drove them back to Salinas.

Near the fire station on Williams Road, one abruptly told him, “Pull over,” and he did so.

Martinez says he heard the shots but never saw what happened. When his companions jumped back in the car, he says, he drove them away in silence while sirens blared behind them.

He later learned that Javier Tovar, 23, had been shot in the back.

Authorities have not named Martinez’s alleged accomplices, nor any other suspects in the crime.

He recalls feeling angry, not because an innocent man was killed, but because he was now wrapped up in a crime he had not consented to. He did his best to forget what happened, push it out of his mind.

A year later, he was in prison again at the same time an entire gang crew in Salinas was charged in connection with a murder at Cap’s Saloon.

When he paroled, Martinez reported to his gang regiment that he was “out and available.”

He and his colleagues arranged to meet at a pizza parlor on East Alisal Street.

Once inside, Martinez noticed the others ordered sodas, not beer. This meeting was going to be serious.

The boss asked if he knew what was going on. “With what?” Martinez answered.

The table fell silent, he says, until another man spoke up.

“Your mom is testifying and turning evidence,” the man said.

Martinez had no idea that she was involved in any of the gang’s business, and his first reaction was anger that his mother had been selling dope for the gang and no one had bothered to ask what he would think.

But he stayed quiet.

“We’re not asking for your approval,” the boss said, “but we need to know where you’re at because she’s going to be whacked and it’s your mother.”

He said what he knew he had to say. “We have to do what we have to do.”

The organization’s leaders weren’t so heartless as to ask Martinez to do it himself, and they promised his mother wouldn’t be hit in front of family.

But the gang did need his help.

Chuca was in a witness relocation program and only Martinez could tell them where she was. They asked for a full report on her location and habits.

Although Martinez readily said yes, something made him wonder if he would really go through with it. He’d been a prominent member of the gang, but he’d never killed anyone, much less a blood relative.

It would take years before he would understand that his mother had committed a truly courageous act, that despite all she’d done to push him into the gang, she was the first with the guts to stand up to it.

Meanwhile, as a newly minted member of the gang’s upper echelon, Martinez had to prove himself by helping his “brothers” carry out their mission.

He would have to choose which family deserved his loyalty.

‘A good robot’

Today, Martinez can’t recall the hours after the order was given, whether he even ate that day or not.

He told himself: This is what happens when people rat. He was, he now says, a “good robot.”

Yet something kept him from reporting back to the gang about his mother’s whereabouts.

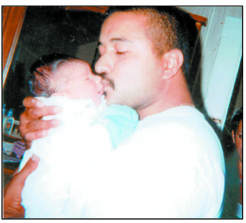

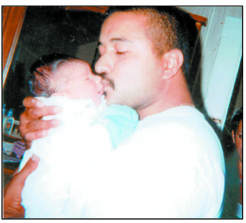

It was then, too, that he learned he was about to become a father.

He says the decision to leave his gang so soon after he’d joined its elite circle came in small steps.

The birth of his son helped Martinez decide to leave gangs for good. / Provided photo

It didn’t happen overnight, and he realized he hadn’t made the decision, it was made for him — he was angry because leaders decided to “tax” young street gang members 25 percent of their criminal income. He was about to get married and become a father. And the gang had just ordered him to help kill his mother.

Despite so many good reasons to get out, walking away would feel like a failure, as if he’d committed a deep betrayal.

“It was like a very bad relationship,” he says. “You ignore all the evidence … You make excuses for being treated wrong. You’re so co-dependent, afraid to be alone, afraid to take a stand, to be confident and say, ‘Hey, I don’t deserve this, you are no good for me.'”

He told himself he was a gangster, so tough he could go through with a hit on his mother, but always, he says, “some sliver of goodness” stopped him from following through.

“That didn’t make me gangster,” he says now. “It made me incredibly stupid.”

It was the impending birth of his son, he says, that pushed him to a decision.

He’d stand outside smoking, looking up at a canopy of stars and think, “I’m going to be a father. There’s still hope.”

With his new wife supporting his decision, Martinez walked into his parole agent’s office and told him, “I’m done. I’m dropping out.”

Permanent changes

After Martinez decided to leave his gang for good, the road to becoming “normal” was far from easy. In fact, it was pretty bumpy.

He was grateful the gang’s leaders respected his decision to focus on family. As long as he didn’t snitch or compete with their drug business and other crimes, they left him alone.

After his second child was born, he turned once again to his drugs of choice, cocaine and methamphetamine, when his relationship with his wife began to unravel.

By 2006, he landed back in prison after an argument with his wife turned physical.

This time, he decided, he had to make permanent changes.

He underwent counseling in domestic violence and relationships, parenting and substance abuse.

Soon he was trained to facilitate nonviolent conflict resolution. He co-founded “Freedom and Choice,” a men’s accountability group for inmates at the state prison in Jamestown.

He was a trained counselor for the “Seeking to Educate Endangered Kids” program, which provided mentoring and counseling to teens on probation.

He was especially moved, he says, by a course run by Criminon International, a group that runs prison and jail workshops addressing “the causes of criminality and restoring the criminal’s self-respect through effective drug detoxification, education and common sense programs.”

He discovered that the leadership skills he’d developed while in the gang were now useful for helping others get their lives together. He earned commendations from the associate warden and has a pile of certificates to prove it.

He earned a new moniker, “Justful Johnny,” because he had a reputation for being fair and holding himself accountable.

In 2008, Jamestown’s Associate Warden Ty Rawlinson wrote that Martinez was “instrumental in creating a new culture in this facility and quite possibly the California prison system.”

While he was locked up, he read a book about how to find happiness. It offered simple guidelines: not harming others; obeying the law; setting a good example.

Things normal people take for granted, he told himself. He began to consider whether he might one day be able to live a normal life.

He would soon discover that the more his prospects began looking up, the more that murder he’d been a part of would haunt him.

Read part two: While he is in jail awaiting trial, Martinez overhears a news report that his mother has been shot and killed. He will listen to her memorial service on a phone in jail.

—-

All contents ©2011 MONTEREY COUNTY HERALD and may not be republished without written permission.

——